Just Where in the World is America's Military?

While it's physical reach is often exaggerated, troop presence alone understates the global influence of the United States Armed Forces

The recent announcement of President Biden’s plan to withdraw all remaining U.S. forces from Afghanistan by September 11th of this year was met with the predictable cavalcade of reactions, not an uncommon one among them being a collective sigh of relief that the “end to the longest war in our country’s history” is seemingly now in sight. The envisioned withdrawal, itself an extension of the exit date originally scheduled for this month by the previous Trump Administration following negotiations with the Taliban, might however still leave some cynical towards the prospect any substantial change in U.S. foreign policy, owing to the otherwise large American military presence abroad.

Over the years I’ve seen online memes like the above purport something along the lines of how the United States has more than 800 military bases abroad, not to mention the presence of the innumerable American soldiers at these installations and other locations, some of which are not even publicly disclosed, and in doing so has become an empire of sorts. Though I consider myself critical of U.S. foreign policy, up until now I had not bothered to verify these allegations. Often new claims are made on the Internet faster than they can be checked for accuracy, which if they turn out to be false or exaggerated, can discredit causes that otherwise have a good factual basis, and this is especially true when it comes to those made of the United States’ activities overseas. So, in light of the President’s statement and its relevance to the American military presence globally, I’ve taken it upon myself to present the most complete and truthful illustration of the actual scope of America’s armed forces outside of its state borders. The figures therein are the most current as of this writing, or May 1st, 2021, and as the situation continues to change, I might update this article in light of new information on the issue in the future.

U.S. Troop Presence, by the Numbers

For this section, I mainly rely upon data from the Defense Manpower Data Center, or DMDC, a bureau for the Office of the Secretary of Defense that collects statistics mainly pertaining to Department of Defense (DoD) personnel and related topics. Included are figures on U.S. soldiers deployed domestically and overseas, which are published on a quarterly basis. The numbers I draw from are from December 2020, the most recent data available.

According to the DMDC , there were some 170,026 active duty military personnel deployed overseas as of December of 2020. U.S. territories are included in this figure, and I am taking them into account as well considering that they are not provided the same political rights and representation as U.S. states and hence are concordant with the “empire” thesis. That being said, in addition to the 170,026 active duty soldiers serving abroad, there are an additional 19,412 reserve and National Guard personnel stationed overseas as well, mostly in U.S. territories, who, while not performing a full-time position in the military, can be deployed into combat at any time. Altogether this gives a figure of 189,438 combat-ready military personnel stationed outside of U.S. states, this being relative to a total of the 1,981,931 relevant personnel for the DoD, or just under nine percent of all combat-ready personnel being placed abroad. By contrast, in September 2008 there were a total of 446,117 of these personnel abroad, or nearly a fifth of all active-duty and reserve soldiers. The ratios of soldiers abroad to those stateside for each period were, respectively, 1:10 and 1:4, evidently a big shift between the two dates.

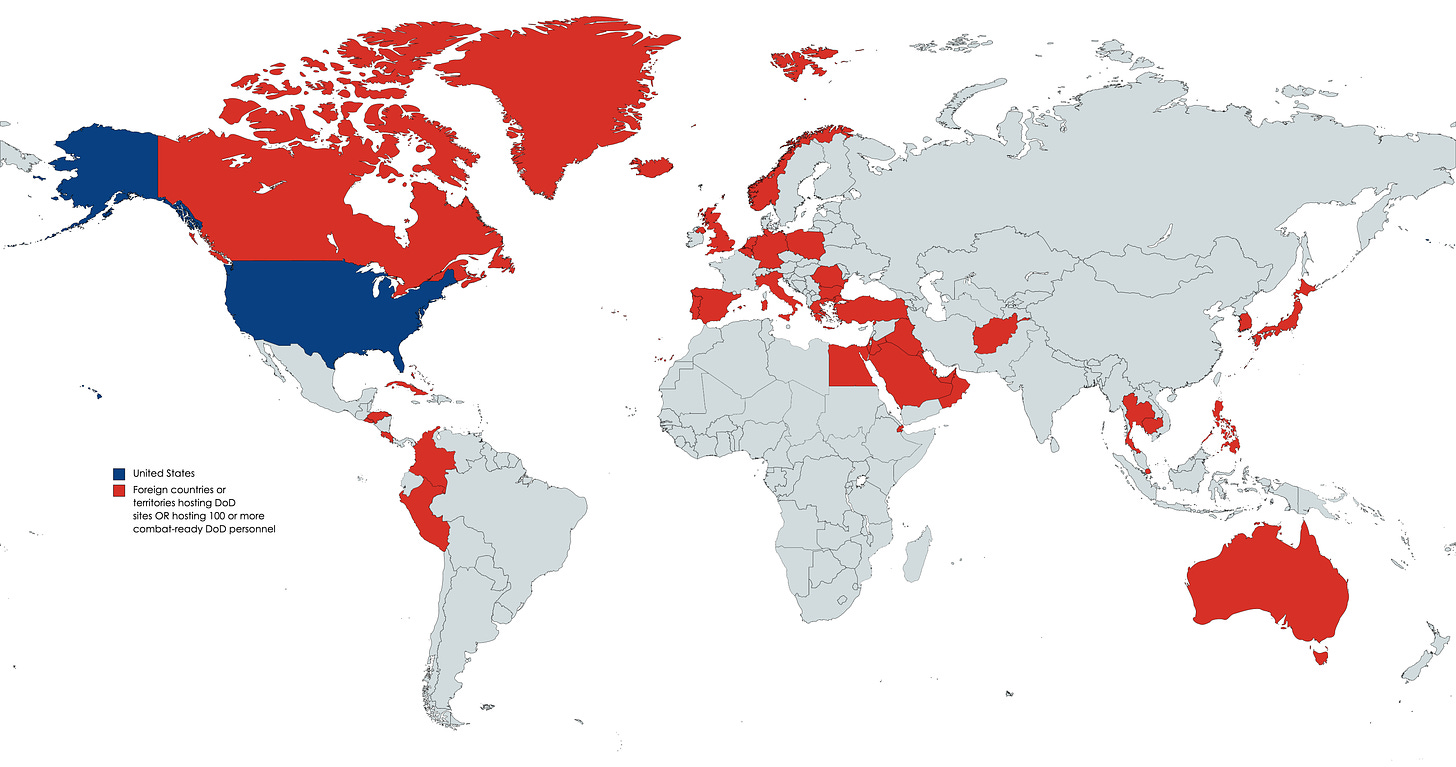

In terms of specifically where U.S. soldiers are stationed overseas, Japan was the single largest destination, with 56,748 active-duty and reserve personnel being located there. Japan by itself accounted for more than a quarter of all combat-ready U.S. personnel stationed abroad. Additionally, the top three countries having a U.S. troop presence, Japan, Germany, and South Korea, alone constituted more than 62% of all overseas-based American military personnel, or 117,175 soldiers. The next locations with the greatest number of combat-ready personnel, Italy, the U.K., and Guam, a U.S. territory, increase this proportion to 78%. If Guam is excluded in place of Bahrain, the figure is mostly unchanged, meaning that just six countries account for more than three-quarters of all U.S. soldiers deployed abroad, at least as of December of last year.

Interestingly enough, only a handful of countries listed have 1,000 or more combined active duty or reserve U.S. soldiers. They include the previous six listed, Spain, Kuwait, and Turkey. Most countries in fact include only several hundred and more often one hundred or less combat-ready personnel within their borders. The bulk of the U.S. foreign military presence when it comes to manpower, then, can be said to be concentrated in ten or so countries and territories. On the other hand, the DMDC stopped publishing a count of its employees stationed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, where there are active hostilities involving U.S. forces, at the end of 2017,1 though it is suspected that between these three there are several thousand active-duty personnel alone. Indeed, a press release from the Department of Defense in January covering the same period as the DMDC report confirmed that there were 2,500 U.S. soldiers each in Iraq and Afghanistan. As for Syria, the Council on Foreign Relations’ Global Conflict Tracker for Syria estimates that there are 500 soldiers in Syria at this time, providing for a total of 5,500 troops for the three countries. The DMDC’s December 2020 report meanwhile includes 5,294 active-duty personnel in “unknown” locations, which tracks closely with the other figures given for Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria.

As for the U.S. military presence in the Middle East, where both U.S. military might and public perceptions of armed conflict have been focused since the 1990s, the latest figures offer a more nuanced picture. The United States Central Command, or CENTCOM, whose area of operations overlaps with most countries traditionally considered part of the Middle East, as well as Afghanistan and other Central Asian states, houses a total of 7,840 combat-ready U.S. military personnel, this in addition to 5,500 or some semi-secret soldiers partaking in operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. The numbers for the published figures within CENTCOM countries range from just five in Yemen to as many as 4,103 in Bahrain, the largest for the entire division. Including the estimated 5,500 soldiers in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, combat-ready personnel deployed in CENTCOM countries account for only seven percent of all such U.S. personnel deployed abroad, and less than a percent of all relevant DoD personnel. More than a decade earlier, in September 2008, the corresponding numbers were 239,478 soldiers throughout CENTCOM’s area of operations, a far-cry from the situation at the end of 2020, with this number representing just over half of all combat-ready U.S. personnel deployed abroad and a tenth of the total applicable manpower for the entire DoD at the time.

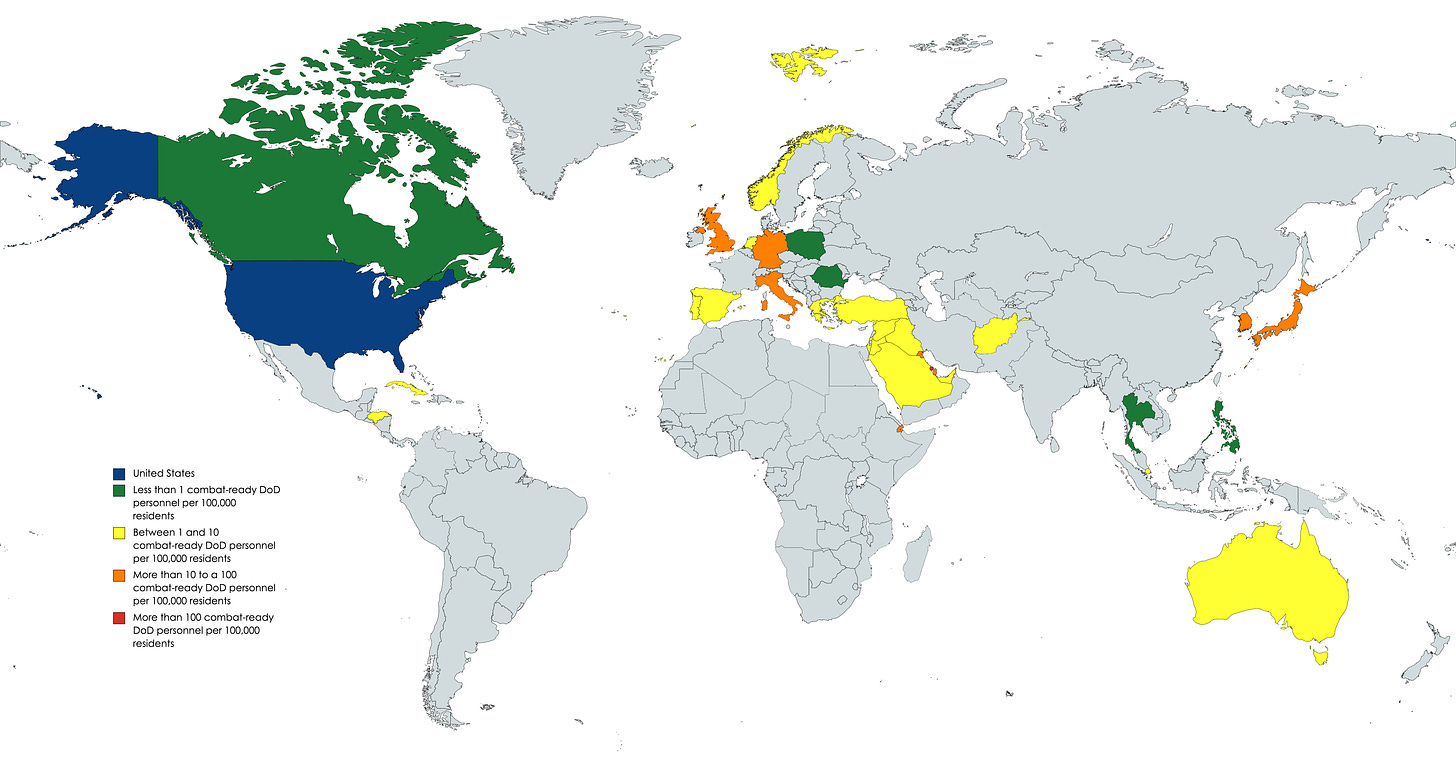

As far as U.S. troops per capita are concerned, in countries hosting at least 100 combat-ready DoD personnel, Bahrain has by far the most of any country, and by extension in CENTCOM, at 241.12 U.S. soldiers for every 100,000 of its residents, which translates into more than 0.2% of its total population being active-duty or reserve personnel of the U.S. Armed Forces. The Philippines in turn has the least compared to its population, with only 0.13 combat-ready DoD personnel for every 100,000 residents. Within the CENTCOM region, Israel, excluding the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT), is the least saturated with U.S. military personnel at only 1.08 troops per 100,000 residents. If the population of the OPT were to be included, this number would be even smaller.

It can thus be concluded that, in comparison to the first decade of the twenty-first century, at least as far as raw manpower is concerned, the United States Armed Forces has substantially reduced its global footprint, with the bulk of its human presence being limited to relatively few countries and U.S. territories. Still, combat-ready DoD personnel continue to be present in most foreign countries. When it comes to the Middle East in particular, this trend is also observed with the U.S. military having just a fraction of the active duty and reserve personnel located there as it did decades prior, with the presence being concentrated mainly where there are ongoing combat operations as well as a few states in the Persian Gulf. The Department of Defense’s decision to classify troop presence in the former beginning in 2017 has made it difficult to ascertain the number of relevant personnel in these countries, but estimates gauge that there are several thousand or so. However, as we shall later see, evaluating the global extent of the U.S. Armed Forces by troop numbers alone is highly imperfect in quantifying and scrutinizing its impact.

U.S. Military Bases, by the Numbers

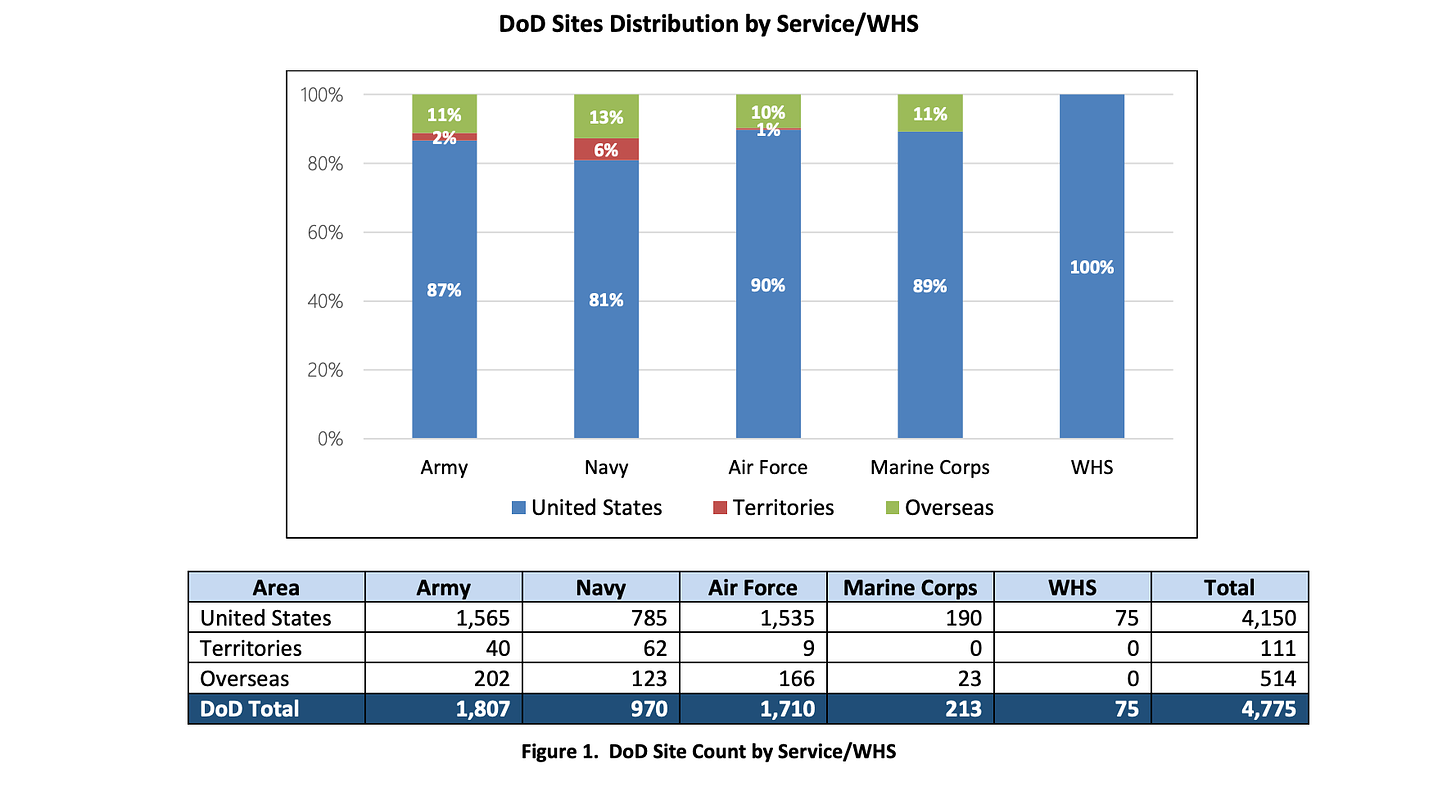

To ascertain the number of military bases the United States maintains abroad, I draw on data from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Sustainment’s Base Structure Report (BSR), the most recent of which was published for the fiscal year 2018. The report defines DoD properties broadly as sites, stating

A specific geographic location that has individual land parcels or facilities assigned to it. Physical (geographic) location that is, or was owned by, leased to, or otherwise under the jurisdiction of a DoD Component on behalf of the United States. A site may be contiguous to another site, but cannot geographically overlap or be within another site. A site may exist in one of three forms: land only – where no facilities are present; facility or facilities only – where there the underlying land is neither owned nor controlled by the government, and land with facilities – where both are present

and installations as

A military base, camp, post, station, yard, center, homeport facility for any ship, or other activity under the jurisdiction of the Department of Defense, including leased space, that is controlled by, or primarily supports DoD’s activities. An installation may consist of one or more sites.

In order for a site to qualify as an individualized entry in the BSR, it must be

located in a foreign country must be larger than 10 acres OR have a PRV greater than $10 million to be shown as a separate entry. Sites not meeting these criteria are aggregated as an “Other” location within each state or country.

To paraphrase a 2015 article, these installations can range from small radar facilities all the way to massive bases that in some cases resemble small cities. Accordingly the BSR classifies sites as being small, medium, large, and “other” based on PRV, or “plant replacement value” in U.S. dollars. According to the BSR, whether located in U.S. states, U.S. territories, or foreign countries, “small” DoD sites constitute the lion’s share of military property.

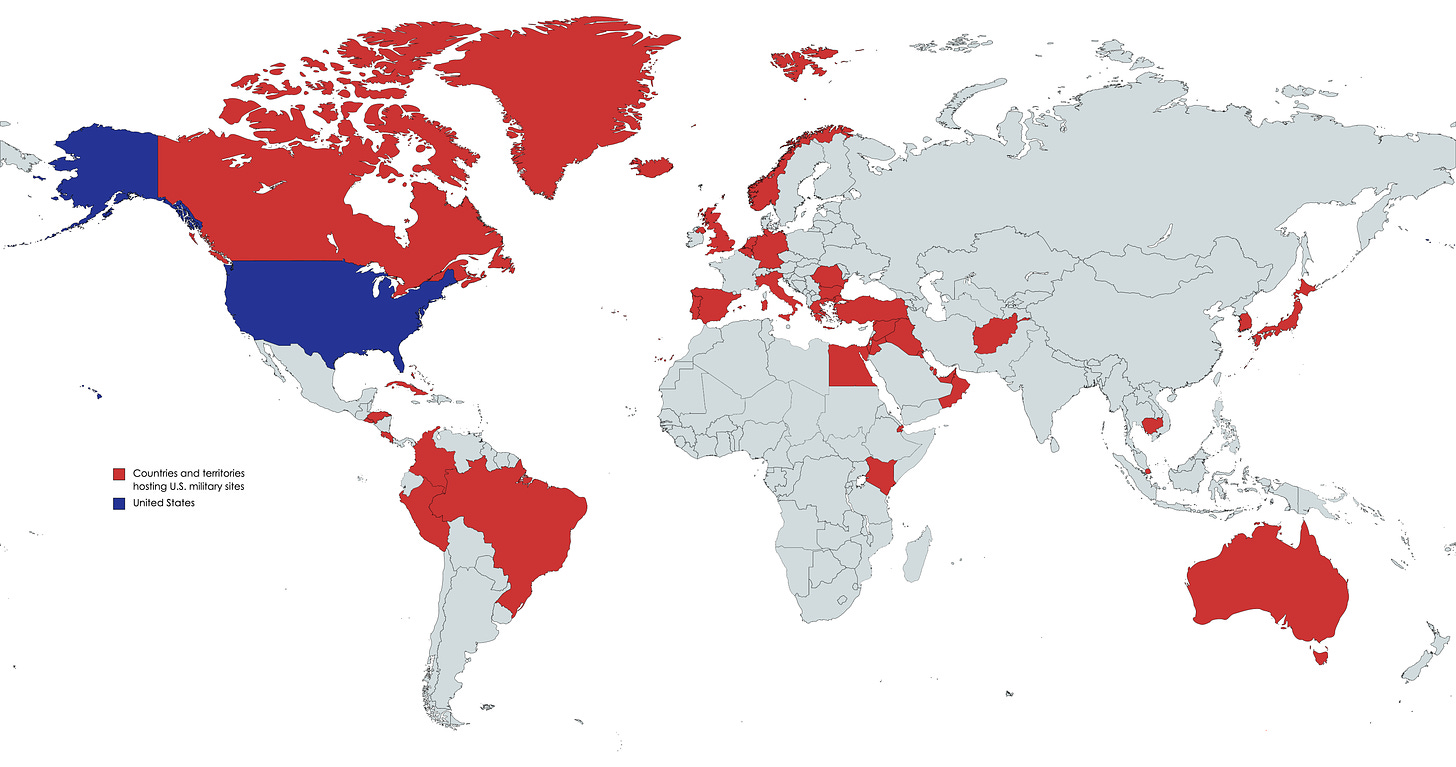

In sum, there are a total of 514 DoD installations overseas, somewhat less than the aforementioned 800 figure but still pretty high, and by far the most of any country in the world. Adding the number of installations in U.S. territories in turn yields a figure of 625 sites outside of U.S. states. Even if “military base” here is narrowly defined as “large” DoD sites with a PRV of $2.067 billion, the U.S. still maintains twenty-four bases in foreign countries and territories and three in U.S. territories as of fiscal year 2018.

From the same period, there were 45 foreign countries and territories hosting U.S. military sites. Amongst the countries and territories doing so, the numbers in each ranged from just one in several, such as in Aruba, Cambodia, Bulgaria, and El Salvador, to more than a hundred in Germany and Japan. Other overseas locations with twenty or more DoD sites include Italy, Portugal, and the United Kingdom. However, as this BSR was published after the DoD directive to stop publicly reporting the quantitative details of military operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria took effect, sites located in those countries are not described. I was unable to find any consistent primary source or other reliable information on these sites, or if they otherwise even qualify as such per being “owned by, leased to, or otherwise under the jurisdiction of a DoD Component on behalf of the United States.” Because of this, these sites surely jack up the official 514/625 figure, but unfortunately I am unable to count them in any subsequent analyses because of the lack of consistent information on them, even though they are known to exist.

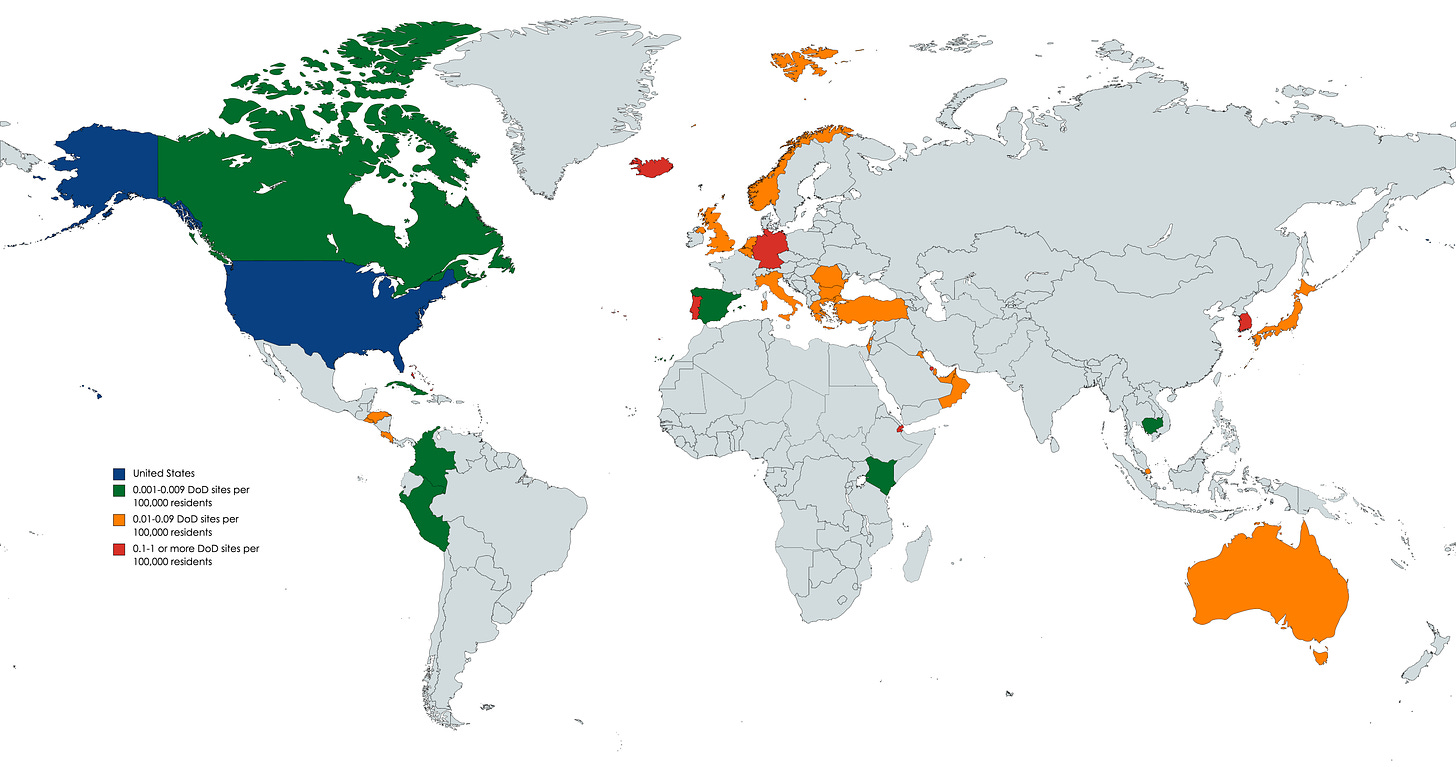

By comparing U.S. military base presence in fiscal year 2018 to the population of the host countries from the same time period, we can derive DoD sites per capita. The Bahamas had the most U.S. military sites per capita of any country at 1.57 for every 100,000 people, though the country has a population of less than a million. Among countries with more than a million people, Bahrain is the most militarized in terms of DoD sites, with a presence of 0.8 sites per 100,000 residents, just as it is when measuring by U.S. troop presence. Those with the smallest U.S. military site presence per capita are Kenya and Egypt, each with roughly 0.001 sites per capita.

It should be noted of course that these figures are based on known sites, and even excluding those in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria do not account for installations and other properties that the Department of Defense keeps secret around the world, which if known likely would make the infamous 800 number appear more tenable. Also not included are NATO and other military sites with combat-ready DoD personnel that are not primarily owned or leased by the DoD or supportive of its activities. Furthermore, it must also be pointed out that not all DoD sites mainly host combat-ready DoD personnel, nor are combat-ready DoD personnel always stationed at sites owned or operated primarily by the DoD, such as in Saudi Arabia, which as of December 2020 hosts 474 U.S. troops despite not having any known BSR-listed sites in FY2018. With all of this being said, it must be emphasized that all of these estimates are therefore tentative and highly subject to change, especially in light of the President’s announcement.

What Troop Levels and Base Presence Don’t Show

So far it can be said that the centerpiece of the “empire” thesis has been born out, namely that the United States has more soldiers outside of its borders and maintains more foreign military bases than any other country in the world, and possibly in history as for the latter. The corollary to this of course is that the U.S. troop presence is generally concentrated in a smattering of countries and the at least 514/625 American military bases outside of U.S. states is lower than in decades past, though the Department of Defense’s hush-hush attitude on this since 2017, at least towards Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, has made this incredibly difficult to verify. Regardless, viewing the DoD’s physical and human capital at face-value masks its true reach abroad.

It should go without saying that the United States still maintains the largest national defense budget (in absolute terms, though not as a percentage of GDP) of any country on the planet, which is greater than the next several combined, most of which are allied states. What’s more interesting though is when one digs into the categories of what the military/defense budget is actually being allocated towards.

In 1962, at the height of the Cold War, military personnel accounted for nearly a third of the then-$5.23 billion defense budget.2 Meanwhile, the cost of operation and maintenance (O&M) during the same time was just over 22% of the entire cost for national defense. By 1991, the year of the Gulf War and the large-scale introduction of U.S. ground forces into Southwest Asia, O&M had eclipsed military personnel as a proportion of the defense budget at 37.2%, with the latter being only 30.5%. For this year’s defense budget the disparity between military personnel and O&M has enlarged even further, with personnel projected to account for as little as 22% of defense spending and O&M for 38.4%. Furthermore, the percent of government outlays devoted to the R&D component of the defense budget has also slightly increased, from 12% in 1962 to 13.6% today.

What this effectively means is that the military today is less reliant on manpower in percentage terms than it was sixty or even thirty years ago. In other words, with the proliferation in technologies and systems such as unmanned aerial vehicles (drones) and cyber-warfare capabilities, the U.S. military is able to more with less, as far as manpower is concerned. The DoD for instance is able to accomplish the same military objectives as it was in the 1990s with three thousands U.S. soldiers stationed in Saudi Arabia with roughly only a tenth of that today, and probably even more for that matter, all due to the relative increase in spending on operation and maintenance and R&D within the national defense budget since then. The military now requiring less human inputs today than in years prior says nothing about its global reach, except that its likely even greater than it previously was, just not as noticeably.

Another oft-overlooked aspect of the U.S. military’s true scope abroad is the role that private military contractors (PMCs) fulfill in carrying out operations on its behalf. These contractors can sustain casualties without having the same level of public notice as those inflicted upon uniformed DoD personnel, and hence can hide the true level of participation of the military in activities overseas. In light of events such as the planned U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, some commentators warn that these conflicts are not actually coming to a close, but are rather merely “privatized” to deflect media scrutiny of warfare as part of a neoliberal world order.

Official reporting of DoD contractors, their numbers abroad, and their activities is scant, but the modest data that does manage to trickle out does provide a general picture of what’s going on. In particular, some data does exist on PMCs in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, as it just so happens. What is publicly known depicts a mixed picture of the circumstances as they stand. As known from the most recent data published for April of this year, the three countries altogether have a combined contractor presence of 21,521, with a total of 37,597 contractors throughout CENTCOM’s area of operations.3 In all of the named locations, most of those present are not U.S. citizens. Looking at the sheer number of contractor deployments alone, however, can be misleading.

Afghanistan, as of last month, had up to 16,832 DoD contractors within its borders, but only a fraction of these, or 2,856 are private security personnel, and of these, 1,520 are actually armed. These are roughly evenly split between U.S. citizens and third-country nationals, with another 243 being locals. To my further surprise, Iraq and Syria, which are recorded together, have just 66 private security contractors between them, and it is not noted whether they are armed. Most of the private contractors in each of the three locations are civilians involved in relatively mundane work, such as food service and transportation. It ought to be repeated, though, that this is just what has been officially published by the Department of Defense, and obviously does not include PMCs in other countries in the CENTCOM region much less those outside of it, like Somalia, where the relevant information remains classified but highly sought after. It remains unknown how these dynamics will continue to unfold as time marches on.

In sum, even taking into account all of the data shown here as well as Biden’s stated commitment to withdraw from Afghanistan by September 11th, the U.S. military will continue to remain a dominant force, whether it be in technological improvements or in private contractors operating semi-clandestinely across the globe, or some other less known capacity.

Coda

The basics of the “empire” thesis, put forth by critics of U.S. foreign policy in the form of a globe-spanning military personnel and base presence, are valid , though far more complex, at least officially, than frequently publicly imagined. Much of this analysis, as has been displayed, is highly contingent though on the limited nature of the information on military activities that the Department of Defense and other government agencies decide to release, especially as of the last several years. For Americans and others to better evaluate the real effects of the United States Armed Forces outside of its borders, an effort should be made to ensure full transparency of its activities by pressuring the relevant government officials to make it so. Otherwise, I’m just as clueless as anyone else.

*As I’m open to updating and improving this article in the future, I encourage readers to bring to my attention any new data or that such was previously unnoticed on my part in order to paint the most accurate picture of this issue as possible.

**I noticed post-publication that the map depicting countries with DoD sites or at least 100 combat-ready personnel does not highlight Syria, even though it should.

Peters, H. M., & Plagakis, S. (2019). Department of Defense Contractor and Troop Levels in Afghanistan and Iraq: 2007-2018. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

GOV, B. (2021). Historical Tables.

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Sustainment. (2021). CENTCOM Quarterly Contractor Census Report, April 2021. ODASD.