Assessing Tucker Carlson's claims about the electoral effects of immigration

The Primetime TV's hosts concerns about immigration and voting are largely improbable and unfounded.

After the April 8th, 2021 edition of Fox News Primetime, firebrand conservative television host Tucker Carlson and his guest Mark Steyn were quick to find themselves in hot water for allegedly referencing a white nationalist conspiracy theory known as white replacement, the basis of which holds that there is an effort to intentionally and systematically ‘replace’ the white populations of majority-white countries, including the United States, with non-white people in order to politically disempower said white populations. Carlson preemptively countered this accusation on the program itself, arguing that race was not his focal point, but rather concern that the Democratic Party was encouraging immigration to the United States in order to score electoral victories over their Republican and conservative opponents. Nevertheless, critics of Carlson and Steyn insisted that they were dog-whistling racism, and this in turn was accompanied by calls in some corners for Carlson’s firing from Fox News. Carlson responded to the accusations with a follow-up segment several days later, largely reiterating his earlier statements.

Because I personally have a very high bar for accusing someone of racism or bigotry in general, and Carlson maintains that his concerns are political and cultural rather than racial or ethnic, it is for this reason that Carlson’s allegations regarding immigration and electoral politics ought to be evaluated from an objective and non-racial perspective. For the sake of clarity, I am here referring to immigrants as people born outside of the United States and at some later time migrated to the United States, commonly known as first-generation immigrants, rather than the children, grandchildren, or other U.S.-born descendants of these immigrants, as these are not immigrants in the strict sense. As some readers may argue that in a broader sense these populations are indeed immigrants, I will remind them that this article seeks to be the most charitable and non-racist interpretation of Carlson’s comments as possible, and as such, am only referring to people who literally immigrated to the United States themselves. The purported Democratic benefit gained by immigration can be operationalized as immigrant support for Democratic candidates at the polls. Finally, the analysis conducted herein will be conducted on legal immigrants only, as Carlson and Steyn discuss how the Democratic Party is purportedly legally, albeit in their view, unscrupulously, inviting immigrants in in order to win elections.

The findings therein suggest that the scenario Carlson is apprehensive of are predicated upon a multi-layered, lengthy, and complicated process by which immigrants in the United States go through the multiple steps necessary to vote in American elections, and in fact actually end up doing so. Even among those immigrants who do eventually go to the polls, the outcomes Carlson is concerned about are far from guaranteed.

From X country to the American ballot box

If Carlson is considered about the effects of immigrant voting, then the topic is of course intimately tied to that of citizenship. Under U.S. law, in order to vote in federal elections (President, Senate, and House of Representatives), one must be a citizen of the United States. This legislation does not apply on the state level, however, every U.S. state since 1926 has legislation barring non-citizens from voting. On even smaller levels of government, the laws are a little less restrictive, though for the purposes of this writing we can assume that this is not what Carlson was referring to, nor do the laws in question significantly differ from those on the federal and state levels.

The question of obtaining U.S. citizenship outside of birthright and its relation to immigration is thus highly relevant here, and requires a brief explanation of the U.S. immigration and naturalization system. The present system is largely based on the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, otherwise known as the Hart-Cellar Act after its congressional sponsors (ironically, despite immigration, legal and illegal, coming predominantly from Latin America to the consternation of some commentators, since the legislation’s passage, Hart-Cellar was in fact the first federal piece of immigration law that limited immigration from the Western hemisphere). As of 2019, legal permanent residency, or LPR, status (a general prerequisite for receiving U.S. citizenship by naturalization) is afforded to prospective immigrants on the basis of family reunification, employment, and to a lesser extent humanitarian concerns (think asylum-seekers and refugees)1. The combined cap for entry visas for the employment and family reunification visas in that year was 675,000, not counting certain family members that recipients in the latter category can sponsor. These spots are not always filled, of course, and the amount of time between the application for and the actual granting of LPR status varies significantly based on the type of visa and where the application is made. In fact, the moderately pro-immigration American Immigration Council found in 2018 that in many cases the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) provided inaccurate processing times for various LPR visas to the public, the given estimates being 10 to 19.5 months for employment-based visas and 10.5 to 23.5 months for family-based visas, or in other words ten months to nearly two years2. However, later estimates from the USCIS gave even more varied estimates, from 7 to 33 months, or nearly three years. This, of course, assuming that prospective applicants satisfy the relevant eligibility requirements. Keep in mind these are estimates of the time it takes to receive legal permanent residence status rather than citizenship, which is of course necessary for voting.

These conditions can be sidestepped entirely, on the other hand, if one’s concern is about non-citizens voting, including illegal immigrants. Non-citizen voting, of course, is axiomatically illegal under federal and state law, but as any teenager will tell you about drug use, just because something is illegal does not mean it does not occur. A 2014 study3 in the journal Electoral Studies contained the potentially explosive finding that, while relatively rare, non-citizen voting in the 2008 and 2010 elections was significant enough to change the outcome of the electoral college as well provided enough congressional votes to allow President Obama to pass his landmark healthcare reform bill through Congress in 2010. The conclusions were based on an analysis of Cooperative Congressional Election Studies data, a representative sample of the U.S. population in 2008 and 2010. An article the following year in the same journal, however, analyzed4 the same data and found that the authors of the 2014 article had erroneously extrapolated their findings by assuming that the already low frequency event of non-citizen voting as a proportion of the large sample size (32,800 and 55,400 for 2008 and 2010, respectively) translated into sizable non-citizen voting in actual elections, and instead stated “[The] results, we show, are completely accounted for by very low frequency measurement error; further, the likely percent of non-citizen voters in recent US elections is 0”. A follow-up article5 to the original defended the methods used to conclude that non-citizens voted in substantial numbers in the years selected, but one of the authors of the 2015 paper told me that the response did not pass peer review to be published and was further rejected as evidence in a federal court case on voter fraud.6 Furthermore, a literature review7 in 2012 similarly found that voting by non-citizens is exceedingly rare, to the point one is more likely to be struck by lightning. If Carlson is concerned about the effect of immigration on elections, it would be more prudent, as we shall see, to look at the political behavior of naturalized immigrants.

Step 2: Naturalization

It is a fallacy in of itself, though, to assume that all permanent immigrants in the United States eventually obtain citizenship, as the data suggests otherwise. The option of naturalization becomes available to LPRs after living in the United States continuously for five years (three if they are married to a U.S. citizen).8 The process of applying for citizenship itself can take between six months to two years, not all of which are approved. For those counting, between processing time for permanent residency status, eligibility for naturalization, and the conferring of U.S. citizenship, an immigrants ability to vote in American elections can take up to a decade.

With all of this in mind, it should be noted that not all LPRs make the decision to seek naturalization, however. In 2015 it was estimated that some 68% of legal permanent residents were eligible to naturalize in the first place.9 According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) in 2019, the most recent year for which figures are available, the lifetime naturalization rate of immigrants in the United States was 48.7%, or just under half of the foreign-born population in the country having citizenship. 10 During the same year, by cross-referencing the total number of naturalizations11 during that time with the total number of eligible LPRs12 in the country, one finds that in 2019 the total rate of naturalization was 9.2%. Broken down by region, LPRs from North America, which includes Central America, had the lowest rate of naturalization for 2019 at 6.35%. The corresponding lifetime naturalization rates of immigrants from Mexico and Latin America in that year were 32.7% and 40.5%, respectively, similarly the lowest rates for all regions measured.13

Interestingly enough, a multivariate analysis of the factors that influence immigrants to naturalize and vote found that the doubling in naturalization rates in California between 1994 and 1997 could possibly be attributed to what was perceived as anti-immigrant hostility among the foreign-born population.14 Throughout the mid-1990s a series of measures regarding issues like bilingual education and illegal immigrant eligibility for social services were fielded and discussed, yet were widely seen by many as targeting the state’s Latino population, of which a significant portion consisted of immigrants. This, in turn, could have had the effect of causing large numbers of this population to seek U.S. citizenship as a means of protecting their status in the United States. If true, it would be ironic that the already minority rate of naturalization of immigrants, especially those originating from Latin America, could be positively affected by rhetoric perceived to be anti-immigrant. In the case that this is true, Carlson’s vocal concerns about the link between immigrants and undesirable electoral outcomes could be a counterintuitive force in increasing the chances that the foreign-born population has a decisive effect on election results.

Registration and turnout rates among the naturalized population

In order to participate in elections in the United States, one must be registered to vote, and as most states do not have automatic voter registration, a significant portion of the prospective electorate must make a conscience choice to do so. Because of this, there are disparities along several demographic lines in voter registration, including nativity. Based on the 2018 federal midterm elections, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated in that year that naturalized citizens, irrespective of race or ethnicity, were registered to vote at 58.2%, somewhat lower than birthright U.S. citizens on the same measure15, who reported a voter registration rate of 67.8%. Akin to how naturalization rates varied by region of birth, the registration rate of foreign-born U.S. citizens from Mexico and Latin America was the third lowest for all regions surveyed, at 57%. For naturalized Hispanics of any race, the figure was 54.9%.

While it has been established that a majority of naturalized citizens register to vote, that does not in turn tell observers whether or not said persons did in fact go on to vote in a given election. Drawing on the same data, in the 2018 elections the CPS found that of the registered population, naturalized citizens turned out to vote at a rate of 45.7%, compared to a rate of 54.2% for natural-born citizens, again showing a disparity in political participation between the two demographics.16 That being said, the reverse pattern was found at the level of race and ethnicity, with foreign-born Latinos having a turnout rate of 44.2%, mildly higher than that of native-born Latino voters at 39%. Similarly, naturalized Asian voters reported a turnout rate of 43%, higher than their native-born counterparts at 37.5%. Pew Research Center reported similar findings in the 2016 general elections, with foreign-born Asian and Latino registered voters having turned out at higher rates than their native-born counterparts.17

What might explain, then, higher rates of voting in some populations of foreign-born members over that of those born in the United States? Researchers in one study on Latino voters combed over a variety of demographic variables, including nativity, in analyzing voter turnout during the 1996 federal elections and focused on three states, California, Florida, and Texas, each with large Latino and immigrant populations. Holding other factors constant, the authors reported that the higher rates of voter turnout in California among then-newly naturalized Latinos, compared to Latinos who had been naturalized for a longer period of time as well as those born in the United States, was directly related to the turbulent rhetoric surrounding immigration (and in the minds of many, by extension, race and ethnicity) in the state. By contrast, the phenomenon was observed neither in Texas nor Florida because of the absence of such public vocal concerns, despite all three states having similar demographics in this regard.18 In other words, turnout among newly naturalized Latinos was a direct response to what was widely seen as a hostile environment for immigrants (and Latinos), in the form of an effort to protect their livelihood as residents of California. As mentioned previously,19 rhetoric and the public policy surrounding it that is or is perceived as being anti-immigrant may actually have the opposite effect in spurring more naturalizations in immigrant populations, and by extension, wider immigrant participation in the electoral process, what Carlson seems to be seeking to prevent as a means of securing favorable election outcomes for the GOP.

Immigrant voting preferences

Finally, and arguably the most relevant aspect of Tucker Carlson’s argument, is how immigrants eligible to do so actually vote in the United States. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be any publicly available exit polling detailing the vote broken down by nativity, and the pertinent data can only be found in studies comparing political views and participation among racial and ethnic groups with large proportions of immigrants, in this case Latinos and Asians.20

The authors of a 2016 paper analyzing state-level data found that an increase in the share of naturalized immigrants in the voting population negatively impacted Republican success in congressional elections,21 seemingly validating Carlson’s contention that immigration is bad for Republicans electorally. The study goes on to state, though, that in some cases Republicans actually gain voters as a result of the increase of non-citizen immigrants in a given population. This occurs via concerns about the issue that tends to drive Republican votes among the U.S.-born population, though this effect only manifests in elections with very close results. However, a later study by the same authors that looked at county-level data and differentiated between high-skill and low-skill immigrants (respectively those with or without a college education) found that Republicans suffered electorally in jurisdictions that had a greater amount of immigration of the former, but benefitted where there was a larger number of the latter.22 The explanation for this phenomena? The concentration of low-skill immigrants in counties increased fears of economic competition among similarly-situated natives, and hence drove these voters to choose Republican candidates, whereas a corresponding aggregation of high-skill immigrants inspired no such similar concerns. In short, immigration affects election outcomes both directly and indirectly, depending on a variety of circumstances, including to the benefit of the GOP, far from the idea that immigration monotonically aids Democratic electoral ambitions.

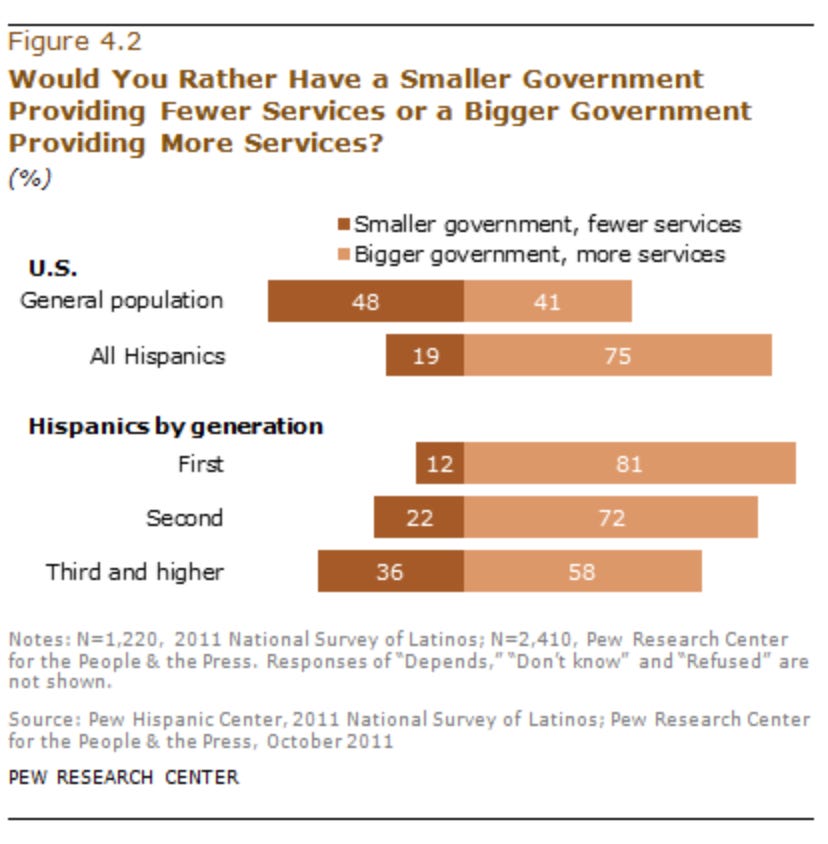

Some may be tempted to point to a 2011 Pew survey purportedly showing that Latinos prefer a larger government that offers more services to a smaller one that offers fewer and hence correlating this with support for the Democratic Party, but this is misleading in several ways. Firstly, the survey is asking about raw preferences, and does not include the multiple conditions necessary for immigrants, including Latino immigrants, must fulfill to vote (deciding to obtain legal permanent residence status, living in the country for five years continuously in order to be eligible to naturalize, registering to vote, and actually showing up to the polls). Secondly, the survey includes all Latinos, irrespective of immigration status, rather than the subject matter which is how immigrants irrespective of race tend to cast their vote, though as stated previously, this data is otherwise difficult to come by. Lastly, the same survey finds that among foreign-born Latinos, the single largest percentage of them self-identify as conservative. One could argue that foreign-born Latino who do vote Republican are just RINOs who don’t care about conservative/Republican values, but the survey data here would seem to contradict that, at least as far as social issues are concerned, and measuring partisan affiliation by support for a “larger” or “smaller” government is already a questionable method of doing so, as Tucker Carlson himself has become known for a kind of conservatism that embraces a larger role for the state.

Pew Research Center’s 2016 National Survey of Latinos did indeed find that a majority, 68%, of foreign-born Latino citizens planned or leaned toward voting for Democrat Hillary Clinton in that year’s presidential election.23 However, the same data set similarly found that among the same demographic, the single largest proportion identified as net conservatives at 34%, with 27% identifying as conservative and 7% identifying as very conservative, contrary to what is often otherwise thought in the popular political consciousness. The accompanying figures for net liberal, on the other hand, were 27%, with19% for liberal and 8% for very liberal. Another study24 based on data from the 2012 general elections likewise found that naturalized Latinos were lopsided in their identification with the Democratic Party, with Republicans/lean-Republicans making up between only 13% to 16% of those surveyed, yet the methodology did not factor in self-identified political beliefs of this population that could have raised more questions about the relationship between actual political views on the one hand and party affiliation and voter preferences on the other.

An analysis of the General Social Survey by the libertarian and pro-immigration CATO Institute25 found that while naturalized citizens for the most part share the same political views as native-born Americans, this was frequently not reflected in the corresponding partisan affiliation, with immigrant citizens tending to favor Democrats. The authors attribute the divergence between political beliefs, and partisan identification and actual voting behavior with the fact that while immigrants may identify as being otherwise politically conservative, it is the conservative, in this case Republican, party’s perceived hostility toward immigration that pushes this population to identify and vote as Democrats. A unique study tested this hypothesis by looking at a sample that included ethnically Chinese immigrants in the United States originating from Southeast Asia, where they likely faced immigration on account of their ethnic background as minorities. The researchers predicted that their previous experiences of discrimination in Southeast Asia, rather than in the United States, would push them toward identifying with the Democratic Party, which is largely seen as the party of that represents the interests of minorities, including immigrants. The results confirmed the hypothesis, net of all other variables, that this group of immigrants was more likely to affiliate with the Democrats.26 If this was just taking into account discrimination in countries of origin, one could only imagine the similar effects discrimination in the host country would have on partisanship and voting. A study of Latino party affiliation in California during the 1990s circumvents the need to imagine, finding that the acrimonious immigration debates of the time were enough to drive Latinos, regardless of nativity, to the Democratic Party,27 replicating the findings of previous studies on the issue in the state.28 29

It would seem apparent now that real or imagined anti-immigrant rhetoric and policy leads to an increase in naturalized immigrants voting, and doing so on behalf of Democrats. The effects of this could likely be mitigated, however, if the Republican Party and its supporters adopted messaging and policy positions that were more accommodating of immigrants and their interests, if there was the will to do so. One could argue in response that opposition to immigration is an inherently conservative value and as such flexibility on the issue would defeat the purpose of conservative values, but if this is the case, opponents of immigration can’t be surprised in the self-fulfilling prophecy that is immigrant rejection of Republican affiliation. Furthermore, one may reply that it is neither the political views nor the party affiliation that is of concern but the geographic, racial, and ethnic characteristics of the immigrants entering the United States, but this would be in conflict with Carlson’s repeated insistence that his concerns are based around voting, not race or ethnicity.

A far-fetched and far from assured conclusion

Tucker Carlson’s argument that the Democratic Party is importing immigrants in order to ensure victory over their Republican opponents is highly tenuous and far-fetched when considering that it is based on several interrelated contingencies, namely that the moment an immigrant sets foot in the United States, they decide to gain LPR status, naturalize, register to vote, and actually end up voting for Democrats, in that order, when this entire process at a minimum takes more than four years, a sizable timescale for a deliberate effort to increase the share of Democratic voters. To recap, among the proportion of immigrants in the United States that do decide to take up legal permanent residency status, less than half make the decision to naturalize, with the median years of waiting to do so being eight for the total population, and eleven for those from Central America, the longest of any region surveyed.30 The lifetime and annual naturalization rates for immigrants from Mexico and Central America in particular are similarly among the lowest. Naturalized citizens, for their part, have a lower voting registration rate than their native-born counterparts, though, registration and voter turnout rates are higher for Latinos and Asians born abroad compared to those born in the United States. Immigrant voters do seem favor Democratic over Republican candidates, but this is in direct contrast to, at least for Latinos, their self-identified political ideology. This disconnect in political views and political behavior can be substantially attributed to the real or imagined anti-immigration stance of the Republican Party, independent of other issues. The nuanced results and sheer amount of temporal space it takes to actually become eligible to vote as an immigrant to the United States hardly suggest that immigrants are predisposed to the Democratic Party, much less that there is a Democratic conspiracy to import immigrants in order to affect electoral outcomes, but rather can be more easily explained by the Democrats’ real or imagined sympathetic position toward immigrants.

All of that being said, this analysis is far from perfect and could certainly be improved upon in several ways. Most importantly is the lack of publicly available data or similar surveying that directly records voting based on nativity, and for that reason I strongly recommend that future exit polls include a country and region of birth response to better assess immigrant voting patterns. There is also the issue of non-citizen voting that sidesteps the process of LPR status, naturalization, and registration altogether, although the data suggests that if occurring at all, it is exceedingly rare, and not enough to affect elections. Finally, in the short-term immigrants do seem poised to favor Democratic candidates, but again this could be mitigated by a change in rhetoric and policy in the Republican Party toward immigration.

The concerns that Tucker Carlson expresses regarding immigration being used as a tool to boost Democratic electoral success, then, seem rather untenable. To the extent that immigrants do favor Democrats, this is not set in stone, and under the right conditions, the votes of naturalized citizens could in fact become a boon for Republicans as well as the types of policies that Carlson supports. For that reason, so long as Carlson’s fears are purely electoral in nature, he has little to lose sleep over.

How the United States Immigration System Works. (2019, October 10). American Immigration Council. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/how-united-states-immigration-system-works

How USCIS Estimates Applications and Petition Processing Times. (2018, July 18). American Immigration Council. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/uscis-data-application-and-petition-processing-times

Richman, J. T., Chattha, G. A., & Earnest, D. C. (2014). Do non-citizens vote in US elections?. Electoral Studies, 36, 149-157.

Ansolabehere, S., Luks, S., & Schaffner, B. F. (2015). The perils of cherry picking low frequency events in large sample surveys. Electoral Studies, 40, 409-410.

Richman, J., Earnest, D. C., & Chattha, G. (2017). A Valid Analysis of a Small Subsample: The Case of Non-Citizen Registration and Voting.

S. Ansolabehere, personal communication, April 14, 2021.

Chicken Little in the Voting Booth: The Non-Existent Problem of Non-Citizen Voter Fraud. (2012, July 13). American Immigration Council. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/chicken-little-voting-booth-non-existent-problem-non-citizen-voter-fraud

1

Blizzard, B. & Batalova, J. (2019, July 11). Naturalization Trends in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/naturalization-trends-united-states-2017#Eligibility

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Foreign Born: 2019 Current Population Survey Detailed Tables, Table 2.17. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2019/demo/foreign-born/cps-2019.html

Baker, B. (2019). Estimates of the Lawful Permanent Resident Population in the United States and the Subpopulation Eligible to Naturalize: 2015-2019. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans.

Department of Homeland Security. (2019). Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2019, Table 21. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook/2019/table21

10

Jones-Correa, M. (2001). Institutional and contextual factors in immigrant naturalization and voting. Citizenship Studies, 5(1), 41-56.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2018, Table 11. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/voting-and-registration/p20-583.html

Ibid.

Budiman, A., Bustamante, L., & López, M. (2020). Naturalized Citizens Make Up Record One-in-Ten US Eligible Voters in 2020. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project.

Pantoja, A. D., Ramirez, R., & Segura, G. M. (2001). Citizens by choice, voters by necessity: Patterns in political mobilization by naturalized Latinos. Political Research Quarterly, 54(4), 729-750.

14

11

Mayda, A. M., Peri, G., & Steingress, W. (2016). Immigration to the US: A Problem for the Republicans or the Democrats? (No. w21941). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Mayda, A. M., Peri, G., & Steingress, W. (2018). The political impact of immigration: Evidence from the United States (No. w24510). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Pew Research Center. 2016 National Survey of Latinos. [Data set]. The Pew Charitable Trusts. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/dataset/2016-national-survey-of-latinos/

Sears, D. O., Danbold, F., & Zavala, V. M. (2016). Incorporation of Latino immigrants into the American party system. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(3), 183-204.

Nowrasteh, A., & Wilson, S. (2017). Immigrants assimilate into the political mainstream. Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

See Lim, P., Barry‐Goodman, C., & Branham, D. (2006). Discrimination that travels: How ethnicity affects party identification for Southeast Asian immigrants. Social Science Quarterly, 87(5), 1158-1170.

Bowler, S., Nicholson, S. P., & Segura, G. M. (2006). Earthquakes and aftershocks: Race, direct democracy, and partisan change. American Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 146-159.

14

18

9